Karl Struss

Pictoral Modernist

- When

- Event has passed (Thu Sep 4, 2008 - Sat Nov 1, 2008)

- Tags

- Galleries, Photography

Claim this listing

Claim this listing

|

Description

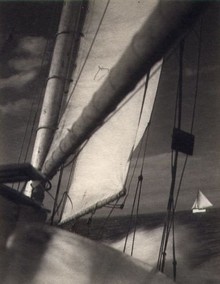

Karl Struss was one of the first photographers to employ modernist compositions in pictorialist photographs. The exhibition features works made by Struss during the period 1909-1929, printed in 1979, and individually signed by the artist.Karl Struss (1886-1981) studied photography with Clarence White from 1908 to 1912. His talent was soon discovered by legendary photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who published eight photogravures by Struss in the April 1912 issue of his journal of photography, Camera Work. That same year Struss became a member of Stieglitz's Photo-Secession, and in 1916 he co-founded the Pictorial Photographers of America. Struss became a successful commercial photographer, with work appearing in Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper's Bazaar. After World War I he moved to Hollywood, where he had a second career as an Academy Award winning cinematographer working for Cecil B. DeMille and others.

Karl Struss worked in the pictorialist syle, characterized by its soft-focus, dreamy prints. Popular in the early decades of the 20th Century, it is considered by many to be the first fine art photography.

Significantly, Struss was one of the first photographers to employ modernist compositions in his pictorialist works, as the photographs being exhibited here illustrate. Photographic modernism, with its emphasis on strong line and abstract form, was to supercede pictorialism in the mid-1920s and beyond. It has been called the first purely photographic form of the art.

John Harvith in his essay “Karl Struss: Man with a Camera” (published in the catalogue of the 1976-77 exhibition by the same name) describes Struss’ modernist pictorial style:

“His analytical eye ruthlessly lops off the peripheral, slices away any remnants of ginerbread. What remains within the frame are sometimes incongruous or anachronistic elements forced into relationship with one another. Without the slightest degree of hedging or wasted motion, these boldly assertive images challenge the viewer to come to grips with their compositional import. Their formal—at times even abstract—conciseness wedded to this juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated elements yields a bracing modernity of vision remarkable in a young man photographing in the decade prior to World War I.”

Karl Struss preferred to compose his final image on the ground glass of his camera, rather than cropping the photograph later in the darkroom. This convention, shared with the great photographer Edward Weston and many of the other Photo-Secessionists, is evident in the photographs in the exhibition. As John Harvith notes, for Struss making a photograph was not about snapping pictures, but rather a careful exercise in preplanning and space-filling.

Interestingly, his skill in previsualizing composition became indispensable in Struss’ later career as a Hollywood cinematographer. In motion pictures there could be no second thoughts once a scene had been captured on film. No cropping, no retouching, no manipulation was possible with the technology of the day.

Comments