A subject no less than life in all of its complexity is the focus of a new exhibition by Katherine Levin-Lau, at artist-owned and -operated art store/gallery The Arsenal.

“I want it to be curious,” Levin-Lau says, referring to her intensely colorful, collage-like interpretations of the detritus of the natural world.

A native of upstate New York, Levin-Lau moved to Santa Barbara as a child. She gleaned early inspiration from local Westmont College, peeking around unlocked science buildings, taking in the vast array of natural oddities on display.

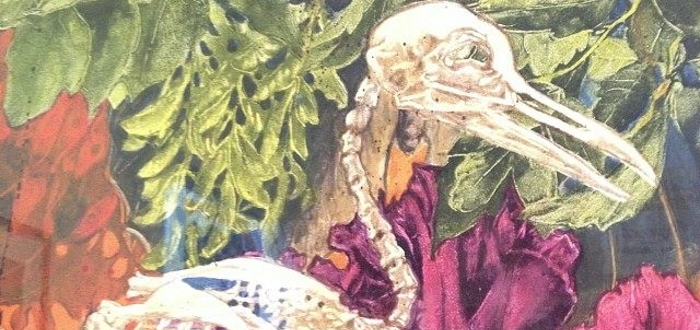

Using typically off-putting images in beautiful ways—such as a skeleton superimposed against a flower—Levin-Lau’s pieces are examinations of the how life and death, the beautiful and dreadful, interact everyday if you dare to look. Her sharp layering of floral arrangements, animal skeletons and sea life play with perceptions and trick the eyes. The drawings manage both to merge objects and isolate them: a floral arrangement at once shadows a skeleton but also highlights it.

What’s most interesting about Levin-Lau’s new work is its subordinate, but still potent, connection to cabinets of curiosities, 17th-century collections of mythical creatures, archaeological items, religious relics or other exotic goods that the were precursors of the modern museum. Just as those old exhibits were driven by aesthetic sense as much as by any real science, Levin-Lau’s collage/bouquet overlaps drawings of naturalistic elements, from skeleton to leaf, to capture both the wonder of objects and the fear of death. The result, to use a contradiction, is a kind of decadent freshness, natural science in the service of studio art.

This “natural” juxtaposition is, as one might imagine, difficult to achieve. Each piece takes a week to create, starting with a monotype printed from an etched zinc plate. Levin-Lau then paints the print in multiple layers, purposefully leaving discrepancies—like small blotches of solvent—that add to the subtle depth of the image. Surprisingly, no black is used; instead a mixture of dark bases such as magenta and orange create a richer, deeper field.

With exhibitions in Europe and across America, Levin-Lau is no stranger to the art world. But she says she has been drawn to San Jose by the city’s growing passion for art. That passion seems widespread—the opening night reception featured a mix of older professionals and a younger, more subversive crowd. The juxtaposition of the gourmet appetizers displayed beneath racks of spray paint reflected both the raw and wondrous elements of Lau’s paintings, as well as the mixed crowds in San Jose’s art scene. For now at least, the area’s art lovers are eschewing any preconceptions of taste or status in their support of compelling local art. That’s good for Levin-Lau, whose art deserves the attention it gets, and for San Jose’s future as an art center.

Review: Cupertino's Peacock Indian Restaurant Delights With Variety

Review: Cupertino's Peacock Indian Restaurant Delights With Variety  Tpumps Brings Its Boba Hype to the South Bay

Tpumps Brings Its Boba Hype to the South Bay