A woman twirls from flowing red curtains a dozen feet in the air. Down the street, a painted lady contorts her multi-colored torso at an angle so the she blends with artwork behind her.

Nearby, a couple of guys with Day of the Dead face paint riff on a guitar and keyboard. And not far off, among the ebullient SubZERO Festival crowd of 15,000-plus—filled with artists, musicians, craft brew aficionados and downtown ramblers—are six men dressed in all black, keeping a watchful eye; some with batons, others Tasers. One carries a gun.

These men are not police.

Rather, they’re part of Silver Star Protective Services, a private security firm that was hired to patrol the June 1 arts and music subculture festival held on South First Street in San Jose. But when a San Jose police sergeant approached one of the security guards that night, some controversy arose.

They were “not only wearing uniform like ours, but also wearing duty belts, batons, tasers, pepper spray or other chemical agents,” says San Jose Police Department spokesman Jose Garcia. “The sergeant expressed concern that they were too similar looking to SJPD and asked them to leave and remove their tasers, firearms and baton, but they could keep pepper spray and mace.”

Henry David Mestaz, president and CEO of Silver Star, says the officer in charge of policing the outskirts of the event was “pretty aggressive” in getting his point across, but there was no altercation.

“Our gameplan was we anticipated thousands of people we’re going to come through,” Mestaz says, noting a reputation downtown events have earned over the years due to younger, disruptive crowds that attended the now defunct Music in the Park summer concert series—to the chagrin of local business owners. “Some of the clientele that was going to Music in the Park were meeting over here afterwards (on South First Street). They were hanging out, drinking, making there way towards the event, and then coming back and fighting. But SubZERO was completely the opposite.”

Under San Jose’s municipal code, police have the authority to regulate which security guards can arm themselves. Silver Star—a new company that may have been “overly excited and enthusiastic,” according to SubZERO organizers Cherri Lakey and Brian Eder, who own Anno Domini art gallery on South First Street—could have gone too far in looking the part of cops in uniform.

The clash between police and the private security company didn’t result in any citations, but it has produced an internal review by SJPD that is expected to reach the city attorney and chief of police’s offices to clarify acceptable uniform and weaponry for outside protective services, Officer Garcia says.

But the events at SubZERO, or actually the lack thereof, seems to speak to the misconception many people have of downtown San Jose, as well as those charged with patrolling it.

“We’re all trying really hard to shift culture, and especially night culture,” Eder says. “It’s just a matter for us that we want to show police we can have events that go really smoothly. And over a matter of time we can all figure this out.”

Part of a new plan by the business community to rebrand downtown is to staff the city’s core with two patrolling officers. However, how these security guards will be paid has kicked off a new fight between police and city officials.

{pagebreak}

Side Jobs

“There’s a lot of competition for customers, residents, commercial tenants, and downtown needs to be putting its best foot forward,” says Scott Knies, executive director of the San Jose Downtown Association.

With businesses struggling to entice customers to downtown over Santana Row and other shopping/entertainment districts, as well as a 22 percent vacancy rate for downtown office space, Knies says the businesses formed a Property Based Improvement District (PBID) in late 2007 to tax themselves and direct funds to combat perceptions as well as reality. The PBID’s self assessment was renewed this week by an overwhelming vote of downtown property owners.

Part of PBID’s plan is to staff the downtown core with two patrolling officers, preferably off-duty police officers.

“Really, there’s no substitute for the professionalism, the training, the way a skilled officer interacts with the public,” Knies says. “They can just kind of read the street from afar. Sometimes they don’t even need to walk down the whole block. Just the fact that they’re on the corner dissipates the problem.”

Jim Unland, president of the Police Officers Association union, agrees with Knies’ assessment, which is why the police union is fighting to have the PBID officers paid at overtime rates rather than the significantly reduced rate of secondary employment positions, which often entail security work for schools and other nightlife areas like Santana Row and The Plant. (More than 60 officers have already applied for the positions.)

“My understanding of the Downtown Business Association is they want them actively patrolling the downtown streets, and proactively taking enforcement actions,” Unland says. “Well, that’s the definition of patrol work. So, they’re trying to replace patrol officers, with essentially off-duty patrol officers.

Tom Saggau, a political consultant for the police union as well as several downtown bars and nightclubs, says some of his latter clients have lobbied City Hall for a greater security presence in the downtown core to little avail. He says without off-duty police, “basically it’s going to be mall cops who are running around causing problems.”

Councilmember Sam Liccardo, whose District 3 includes downtown, rejects any notion that City Hall has resisted a greater police presence. “There’s one person who decides how to allocate officers, and that’s the police chief,” he says, “and I’m not throwing the chief under the bus.”

But some observers on the political periphery say that’s exactly what the police union is doing to Liccardo. The fight between the POA and Liccardo turned personal during the last two years of contentious pension reform negotiations, which ultimately fell apart and resulted in the council forming Measure B and voters passing the measure earlier this month.

Unland recently sent a letter out to POA membership slamming Liccardo for again going after their pay through the PBID patrol program.

Liccardo disputes claims that he was trying to short-sell officers’ pay by classifying the PBID work as a secondary employment instead of overtime.

“Let’s be clear, when you call it patrolling because they’re walking down the street or they’re standing in front of a club with a badge and police uniform, to me it’s a distinction without a difference,” Liccardo says. “ To me, the value of the officers is that there’s somebody there under the color of authority, with the skills and the training to enforce the law.”

Unland and the POA will be meeting this week with the city’s chief negotiator, Alex Gurza, to discuss PBID patrol compensation. While negotiations between the two parties have often gone next to nowhere in the past, the subject of secondary employment carries added significance after an audit in March found wide-spread abuses of the secondary employment program.

An attempt to challenge secondary employment classification for PBID patrol could risk work in other areas, such as schools, shopping centers and other arts and music festivals, Knies says.

“I’m not sure what their argument is, because it seems the scope of work is very similar to the scope of work for a lot of other secondary employment jobs. They’re actually putting their whole secondary employment in jeopardy.”

Dennis Nahat Remembers Ballet San Jose Dancer Tiffany Glenn

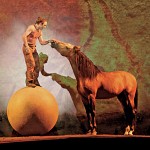

Dennis Nahat Remembers Ballet San Jose Dancer Tiffany Glenn  Cavalia Gallops to San Jose July 18

Cavalia Gallops to San Jose July 18