Back in 1859, British astronomer Richard Carrington reported seeing what is now believed to be the biggest solar storm in history. A cloud of electrons, ions, and atoms escaped the sun’s corona and hurtled through space, eventually hitting the Earth. This affected the aurora borealis, more commonly known as the northern lights. For a brief time they could be seen across the continental United States and as far south as El Salvador. The rush of charged particles also affected electrical equipment, though in 1859, this just meant the telegraph. Household electronics were still a century away.

Since then the world has become more “electrified,” and the impact of these solar storms, even less severe storms, was more widely felt. Solar flares in 1921 and 1960 affected radio and television broadcasts. A major storm in 1989 caused the collapse of the Quebec power grid in Canada, and led to blackouts for as long as nine hours for some six million Canadians.

There have been countless examples of the impact solar flares have had on everything from communications satellites to short wave radio, but none has been as powerful as the 1859 flare, at least until now.

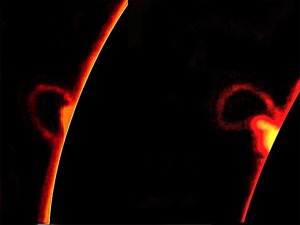

Scientists say that they are seeing a build-up in solar activity, with as many as five storms being witnessed a day. This week, three major explosions were witnessed on the sun’s corona. While this has always been a natural occurrence, never before have people been so dependent on electrical and electronic equipment, and that equipment is most likely to be affected if a major cloud—a “coronal mass ejection” of particles, in scientific terms—hits earth.

It could set off electrical surges, damaging transformers and taking down large segments of the infrastructure. It could also affect the GPS system used by the FAA to oversee flights—this already happened once in 2003. And it could affect communications satellites, knocking out everything from radio to the internet.

The expected cycle of storms could last as long as a decade, say scientists. They call a repeat of a storm the magnitude of the one faced in 1859 and 1921, a “space weather Katrina,” and warn that damages could exceed $1 trillion.

The good news is that for the first time, scientists are also able to keep track of solar storms and determine which would affect the Earth. Upon leaving the sun’s corona, the cloud of particles still has to travel some 93 million miles across space, before it can even reach us. It could do that in just over a day, but more typically, there would be three to four days advance notice. It’s not a lot of time, but it’s enough to take the minimum steps to prepare.

Joseph Kunches, a space weather scientist at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, says that the first of three explosions on the sun’s surface witnessed earlier this week has already passed us. Earth is currently experiencing the second flare, which could result in cell phone glitches and slower internet connection speeds. As for the third flare, Kunches says, “We’ll have to see what happens over the next few days. It could exacerbate the disturbance in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by the second (storm) or do nothing at all.”

Hedley Club Jazz Jam

Hedley Club Jazz Jam