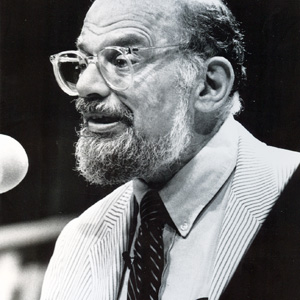

SAVE YOUR MONEY!!!!!!!” Allen Ginsberg told Jack Kerouac in a letter from 1957.

Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” was a hit after a high-profile trial over its presumed obscenity, and Kerouac’s second book, On the Road, had transformed the author nearly overnight into the most popular novelist in America. “God knows what oblivion we’ll wind up in.”

Kerouac and Ginsberg sparked a new kind of American romanticism: Instead of settling down and keeping their bellies full, they would stay hungry and keep looking. They didn’t just wish to be read by America; they wanted to create a new country, a place for the madmen, drug fiends and sex addicts. “I want to write about the crazy generation,” Kerouac wrote to Ginsberg in 1949 of his work-in-progress On the Road, “and put them on the map and give them importance and make everything begin to change once more.” No, they had no idea the trouble they’d end up in.

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters chronicles not only the rise of a still controversial literary movement but also everything left in its wake: the anxieties, pretensions and intimacies of these two icons. A sense of foreboding pervades the 25-year correspondence.

It begins with Kerouac in jail in 1944, on an accessory to murder charge. Ginsberg and Kerouac had known each other for just a few months. Their friend Lucien Carr had murdered their other friend David Kammerer for drunkenly coming on to him one night and dumped the body in the Hudson River. Carr told his friends William Burroughs and a 22-year-old Jack Kerouac about what had happened. None of them said anything to the police. Finally, Carr confessed, and Kerouac went to prison. He married his girlfriend so she would pay his bail.

These were bleak beginnings, but their brush with death and the law made Ginsberg and Kerouac take each other seriously, even when no one else would. They were their own best PR men, showing their work to anyone who would look and helping to get everyone in their group published. Ginsberg’s friendship with poet William Carlos Williams illuminates his blind ambition to be read. “Williams is nutty as a fruitcake,” he wrote in 1952. “It also means we can all get books out.”

Their willingness to use people is not surprising, but the consistency of their self-assuredness is. In the earliest letters, barely out of their teens, Ginsberg and Kerouac had already found their voices, and they knew it, too. “We creative geniuses must bite fingernails together or at least we should,” Kerouac wrote to Ginsberg.

They criticize each other’s writing—not just poems and stories, but the language of the letters themselves—with a severity that makes their harshest critics seem kind. Kerouac calls Ginsberg’s language “peckerhead romanticism”; when Kerouac compares On the Road to Ulysses, Ginsberg tells him, “You’re juss crappin around thoughtlessly with that trickstyle often, and it’s not so good.”

The collection reads like a Dostoyevsky novel: It begins with a murder and ends, essentially, with a suicide (Kerouac’s death from cirrhosis of the liver in 1969). The authors are wild and unguarded, real-life protagonists that never quite made it into the Beat literature: Kerouac, stubborn, paranoid, hot-tempered, but in love with every person he meets; Ginsberg, the horny kid prone to hallucinations and consumed by poetry.

Unfortunately, the letters become sporadic near the end of the friendship, and only some of Kerouac’s decline is on view here. As his popularity rises, the binges become noticeably longer and the writing disintegrates in the haze of inebriation. “When I sawyeouek what I sawk woue and that’s that. I’m drunk. You can see I’m writing this letter drunk.” Ginsberg was no ascetic himself. “Got high on junk last night and though of you,” he writes. “Said myself we must—now we are famous—not get drawn apart by varying fames or worlds.”

Beneath each word collected here is the foreboding terror that even if these two writers could change American literature, it wouldn’t make a difference in their own lives. Kerouac would still get drunk. Ginsberg would still get high. Even at the height of their popularity, the correspondence feels like it’s racing toward a tragic conclusion. It is fitting, then, that these letters are themselves emblematic of the end of an era: This large volume is one of the last major correspondences spanning several decades between two influential writers before long-distance phone calls became cheap.

The book is all about conclusions—the end of a friendship, the end of ’50s paranoia and ’60s optimism, the end of written correspondence itself. Yet what Ginsberg and Kerouac created persists. The legacy of the Beat Generation still saturates American popular culture. Somewhere, a 16-year-old in a used car just discovered On the Road and is about to set off without a destination, in search of a madness that destroyed the best minds of a generation.

Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters

Edited by Bill Morgan and David Stanford

Viking, 500 pages, $35

Opera: ‘Anna Karenina’

Opera: ‘Anna Karenina’  Zero1 San Jose: High Tech Art Utopia

Zero1 San Jose: High Tech Art Utopia